UW researchers sail into the eye of Hurricane Milton

UW researchers tracking Hurricane Milton

When UW researcher Andy Chiodi and members of a multi-state research team stare into the eye of a massive hurricane like Milton, they do so with a mighty army of sail drones.

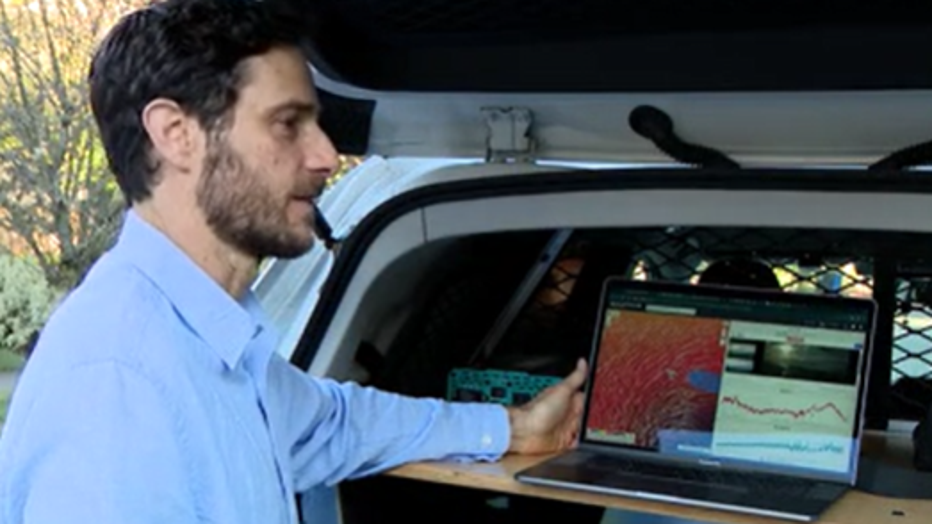

SEATTLE - When UW Senior Research Scientist Andy Chiodi and members of a multi-state research team stare into the eye of a massive hurricane like Milton, they do so with a mighty red army.

"When we get into the storms, it gives us some idea what conditions are like," said Chiodi.

A group of about 10–12 brightly-colored sail drones, armed with high-tech cameras and sensors set sail months ago. The drones are similar to the one pictured below.

Image credit: NOAA and Saildrone

The Saildrones are driven remotely into the heart of the hurricane, to capture data.

"How much spray might be out there what the wave conditions are looking like," said Chiodi.

A Saildrone captured video of monster Milton on Wednesday afternoon, before it made landfall.

Image credit: NOAA and Saildrone

"You are looking at 30-foot waves," said Chiodi. "The storm surge is definitely going to be an issue."

"That’s what it might look like if you are on this thing out there," said Chiodi. "A storm like this has not been seen in this area of Florida for a century."

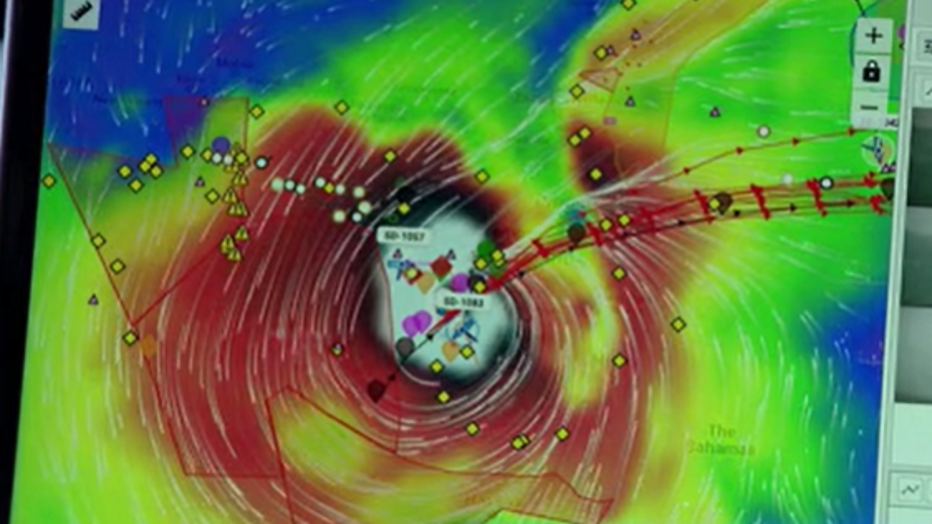

"Where you see the lightest colors, that’s the strongest winds," said Chiodi.

On Wednesday, the massive waves were recorded about 60 nautical miles away from the Florida Coast.

"There’s the entrance to Sarasota Bay," said Chiodi. "I wouldn’t want to be in Sarasota right now."

The drones are part of a collaborative partnership involving Saildrone Inc. and researchers at UW, a sister lab in Miami, and NOAA, with the goal of improving the predictive tools that forecasters use in order to save lives.

"Hopefully improve the models that the forecasters are going to be looking at," said Chiodi.

On Wednesday, another Saildrone was positioned on the eastern side of Florida, to gather data after Milton's exit. A fourth drone was also positioned further away in the Atlantic Ocean to capture images of Hurricane Leslie.

"We are looking at getting two eyewall intercepts on the same day," said Chiodi.

Chiodi is also researching heat and momentum transfer at the surface of the ocean, so one day scientists might know more about what conditions create record-setting hurricanes like Milton.

"In order to rapidly intensify, the storms need to pull a lot of heat, a lot of moisture out of the ocean, so if the models are getting those wrong, we want to know why," said Chiodi.

Image credit: NOAA and Saildrone